Idbury is one of 47 English villages listed in K. M. Briggs, A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales as ‘Places supposed to be inhabited by simpletons’. A marshy strip of field between two streams is still called Cuckoo Pen, showing that at one time the folktale known as ‘The Pent Cuckoo’ was told of Idbury. In this tale, villagers attempt to pen the cuckoo in, so that it will be eternal summer, but the cuckoo flies away just as they seem to be on the verge of success.

listed in K. M. Briggs, A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales as ‘Places supposed to be inhabited by simpletons’. A marshy strip of field between two streams is still called Cuckoo Pen, showing that at one time the folktale known as ‘The Pent Cuckoo’ was told of Idbury. In this tale, villagers attempt to pen the cuckoo in, so that it will be eternal summer, but the cuckoo flies away just as they seem to be on the verge of success.

A few scraps of story and rhyme survive from what was once a thriving folk culture in Idbury, but the main importance of Idbury for folklorists is its place in the recording and revival of the Cotswold morris dance tradition. There was an active Idbury morris side up to the end of the 19th century. The Idbury repertoire (by then merged with that of nearby Bledington) was recorded and published by Cecil Sharp in The Morris Book, and more recently has been studied by Keith Chandler in The Idbury and Bledington Morris: Continuity and Interaction.

According to Richard Bond, who lived at what is now Idbury Farm, talking to J. W. Robertson Scott in 1924, the Idbury morris side around about 1850 consisted of John and William Lainchbury, both labourers, of Idbury; William Toms of Westcote; Benjamin Paxford, also a labourer, of Idbury; and Charles Toms, brother of William, on the fiddle. They practised in the street outside Paxfords, a thatched cottage that was demolished in the 1950s or 60s, which stood between the Old Forge and St. Nicholas church. Bond, born in Fifield in 1842, said that this side “died out before I could have gone with them.” In the 1860s a new Idbury morris side, emerged, included as dancers Jonathan Harris, William Trotman, Richard Bond, and possibly William Lainchbury, the only link with the previous side. The musician for this new dance team was Charles Benfield, born in Bould (a hamlet just down the hill from Idbury), who originally played a pipe and tabor, before switching to the fiddle. It was from Charles Benfield that Cecil Sharp notated the Idbury morris tunes, having first bought the then-elderly Benfield a new fiddle to play them on.

Richard Bond was an important source for Cecil Sharp when Sharp was brought to Bledington and Idbury by Reginald Tiddy before the First World War to record the Idbury-Bledington morris dances. Bond told Cecil Sharp that, ‘Both Idbury and Fifield had a morris side, but they danced exactly the same dances as the Bledington men, and to the same fiddler, Benfield’ – that is, Charles Benfield of Bould.

When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited Idbury in Robertson Scott’s day, staying overnight at the manor of the 10th of September 1923, they transcribed into the Idbury Book the jig ‘Princess Royal’ as whistled by Richard Bond, then aged 81, noting it as ‘one of the Bledington-cum-Idbury morris airs’.

When Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visited Idbury in Robertson Scott’s day, staying overnight at the manor of the 10th of September 1923, they transcribed into the Idbury Book the jig ‘Princess Royal’ as whistled by Richard Bond, then aged 81, noting it as ‘one of the Bledington-cum-Idbury morris airs’.

Maud Karpeles records a remark made by Mr Bond on the 11th: ‘Anybody that has a good ear can see by the tune what the steps are.

The energetic and physically-taxi ng morris dances such as Princess Royal were performed at fetes and holidays, but especially at Whitsun. In 1982, William Paxford of Idbury, grandson of the dancer Benjamin Paxford, told the morris dance expert Keith Chandler that the Idbury-Bledington morris side used to go off dancing at Whitsun, leaving on a Monday morning and staying away for a whole week. Each of them had a new pair of shoes to start off with, and by the time they returned the shoes were worn out.

ng morris dances such as Princess Royal were performed at fetes and holidays, but especially at Whitsun. In 1982, William Paxford of Idbury, grandson of the dancer Benjamin Paxford, told the morris dance expert Keith Chandler that the Idbury-Bledington morris side used to go off dancing at Whitsun, leaving on a Monday morning and staying away for a whole week. Each of them had a new pair of shoes to start off with, and by the time they returned the shoes were worn out.

Morris dancing was not a genteel occupation. The dancers were accompanied by a Boxman whose job was to collect money in a heart-shaped metal tin, which would be most likely spent on beer. One resident of Fifield remembers her mother telling her that a visit from the morris dancers was always looked forward to, as ‘there was sure to be fight.’

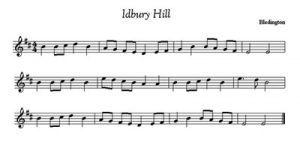

There were 28 dances in the local repertoire, including Idbury Hill, Hey Diddle Dis, Gallant Hussar, Trunkles, Saturday Night, Shepherd’s Hey, Maid of the Mill, Cuckoo’s Nest, Constant Billy, Jockie to the Fair, Old Woman Tossed Up, We Won’t Go Home, Highland Mary, Princess Royal, Lord Sherborne’s Jig, and General Monk’s March. This Idbury-Bledington dance tradition, as recorded and published by Sharp in The Morris Book, has formed one of the principal roots of the English morris dance revival.

There were 28 dances in the local repertoire, including Idbury Hill, Hey Diddle Dis, Gallant Hussar, Trunkles, Saturday Night, Shepherd’s Hey, Maid of the Mill, Cuckoo’s Nest, Constant Billy, Jockie to the Fair, Old Woman Tossed Up, We Won’t Go Home, Highland Mary, Princess Royal, Lord Sherborne’s Jig, and General Monk’s March. This Idbury-Bledington dance tradition, as recorded and published by Sharp in The Morris Book, has formed one of the principal roots of the English morris dance revival.

The very first revival side, started by D’Arcy Ferris at Bidford in 1885, learned its dances from William Trotman, an Idbury man. Jonathan Harris of Bould lent Trotman a set of bells to get the enterprise going.

One interesting visitor who came to Idbury in 1924 and 1925 was Rolf Gardiner, who brought his revival dance troop the Travelling Morrice from Cambridge to perform on the manor house lawn; another member of morris side was Arthur Heffer, the bookseller. Gardiner was attracted to Idbury because, as we shall see for ourselves next month, the village forms a crucial link in the chain of transmission of the morris dance. He was an idealistic young man who, inspired by the wandervogel of post-war Germany, wanted to revive English culture through folk song and dance and healthy outdoor pursuits. At the time of his visits, he was a leading member of the Kibbo Kift Kindred, a grown-up offshoot of the Boy Scout movement, which wanted to revive folk life from beneath the deadening influence of ‘Machine civilisation’.

Robertson Scott was welcoming to these young visitors, but a bit aloof. In her history of Bledington, The Changing English Village, M. K. Ashby records that he was ‘a little taciturn’. He was too astute a man to believe that the problems of the countryside could be solved by hiking and dancing. He may also have suspected a hidden agenda on Gardiner’s side. Around this time Gardiner was on the lookout for a country house where he could found a new movement to turn his dreams into reality. He managed to enthuse quite a few people with his vision, including the writer D. H. Lawrence. On October 11th 1926 Lawrence wrote to him, ‘I think, one day, I shall take a place in the country, somewhere, where perhaps one or two men might like to settle in the neighbourhood, and we might possibly slowly evolve a new rhythm of life’; and on December 3rd the same year, ‘We’ll have to establish some spot on earth, that will be the fissure into the underworld, like the oracle at Delphos, where one can always come to. I will try to do it myself. I will try to come to England and make a place – some quiet place in the country – where one can begin – and from which the hiker, maybe can branch out. Some place with a big barn and a bit of land – if one has enough money.’ If Robertson wasn’t careful, Idbury Manor might just have ended up as just the ‘quiet place in the country’ that Gardiner and Lawrence were looking for.

Robertson Scott was welcoming to these young visitors, but a bit aloof. In her history of Bledington, The Changing English Village, M. K. Ashby records that he was ‘a little taciturn’. He was too astute a man to believe that the problems of the countryside could be solved by hiking and dancing. He may also have suspected a hidden agenda on Gardiner’s side. Around this time Gardiner was on the lookout for a country house where he could found a new movement to turn his dreams into reality. He managed to enthuse quite a few people with his vision, including the writer D. H. Lawrence. On October 11th 1926 Lawrence wrote to him, ‘I think, one day, I shall take a place in the country, somewhere, where perhaps one or two men might like to settle in the neighbourhood, and we might possibly slowly evolve a new rhythm of life’; and on December 3rd the same year, ‘We’ll have to establish some spot on earth, that will be the fissure into the underworld, like the oracle at Delphos, where one can always come to. I will try to do it myself. I will try to come to England and make a place – some quiet place in the country – where one can begin – and from which the hiker, maybe can branch out. Some place with a big barn and a bit of land – if one has enough money.’ If Robertson wasn’t careful, Idbury Manor might just have ended up as just the ‘quiet place in the country’ that Gardiner and Lawrence were looking for.

In fact Rolf Gardiner took over his uncle’s farm in North Dorset, Gore Farm, where he founded the Springhead Ring, a fellowship devoted to organic agriculture, organic living, and of course folk dancing, which still exists today as the Springhead Trust. But Gardiner’s inspiration in the German youth movements of the 20s were to enmesh him in fascism in the 30s, and he is now rather unfairly remembered as a Nazi sympathiser, who is supposed in folk legend to have saved the village of Fontmell Magna from Hitler’s bombs by planting a swastika in the woods to warn away the German planes.

His visits to Idbury were innocent enough, however, and those who remembered the old dance traditions were excited to see them brought back to life. According to M. K. Ashby, Richard Bond was so overcome with the show of morris dancing that Gardiner’s troop put on in the manor garden that, ‘he insisted on making a speech. The dancing was ‘”proper pretty”, he said, and he had never seen Trunkles so well done, and “it takes a bit o’ doin’”.’ Mr Bond then sang the old folk song ‘Arthur o’ Bradley O’, with its comic description of an over-the-top village feast:

The dishes, though few, were good,

And the sweetest of animal food;

There was roast guinea pig,and a bantam,

A sheep’s head stewed in a lanthorn,

Two calves’ feet, and a bull’s trotter,

The fore and hind leg of an otter,

Lampfish, limpets, and dabs,

Crayfish, cockles, and crabs,

Red herrings and sprats by the dozens,

To feast all his uncles and cousins,

Who were so well pleased with the treat,

And heartily they did all eat

To the honour of Arthur o’Bradley O.

In recent years several modern revival morris sides have danced in Idbury, performing Idbury Hill in the village of its birth. Notably, the Ducklington Morris especially learned a number dances from the Idbury-Bledington tradition to perform at the closing event of the first Idbury Arts Festival in 2005. Members of several local families closely associated with the morris, including Harris and Bond, were present to see the Idbury dances performed with vigour and grace.

In recent years several modern revival morris sides have danced in Idbury, performing Idbury Hill in the village of its birth. Notably, the Ducklington Morris especially learned a number dances from the Idbury-Bledington tradition to perform at the closing event of the first Idbury Arts Festival in 2005. Members of several local families closely associated with the morris, including Harris and Bond, were present to see the Idbury dances performed with vigour and grace.

The morris dancers had rhymes as well as tunes and steps associated with the dances. A famous one collected from Idbury by Cecil Sharp is ‘ The Old Woman Tossed Up in a Blanket’:

There was an old woman tossed up in a blanket

Ninety-nine miles beyond the moon,

And under one arm she carried a basket,

And under t’other she carried a broom.

Old woman, old woman, old woman cried I,

Oh whither, oh whither, oh whither so high?

I’m going to sweep cobwebs beyond the sky,

And I’ll be back with you by and by.

Another rhyme, recorded by M. K. Ashby in her history of Bledington, recalls Idbury’s history of village lace-making – which was often in the nineteenth century a pretext for discreet rural prostitution, there being nothing quite so enticing as a pretty girl sitting in a cottage doorway making lace. Ashby says that this quatrain, a parody of Greensleeves, is a fragment of the Idbury Mumming Play, though it may also have been associated with the morris:

Greensleeves and yellow lace,

Get up, you bitch, and work apace.

Your father lies in an awful place

All for the want of money.

It does seem that Idbury did have a traditional Christmas Mummer’s Play, probably performed by the morris side, but we can find no further traces of it. It is not in Reginald Tiddy’s book The Mummer’s Play. This was published posthumously after Tiddy, who lived in Ascott-under-Wychwood, was killed in WWI, and does contain play texts from Shipton-under-Wychwood, Leafield, Icomb, and Longborough. The Shipton play, which is based on the ballad ‘Robin Hood and the Tanner’, contains the lines ‘Green sleeves and yellow lace four monkeys dance apace.’ It is possible that a more complete text of the Idbury play may still exist in Reginald Tiddy’s papers, but we have not been able to ascertain their whereabouts.

The Icomb play is probably similar to that performed in Idbury. A group of mummer’s would take it from house to house, soliciting money at Christmas time. The plays all have nonsense words and plenty of fighting. The Icomb version is opened in fine style by the leading man, with the words

In comes I Old Hind-before,

I comes fust to open your door.

I comes fust to kick up a dust,

I comes fust to sweep up your house.

A character acting the Royal of Prussia King comes in, and after more nonsense has a fight with John Bull Robin, in which the Royal of Prussia King is mortally wounded. The leading man then calls for a doctor, and the Doctor appears:

I am the Doctor come from Spain

To fetch the dead to life again.

With the help of another character named Jack Finney, the doctor ministers to the King, pretending, for instance, to extract a horse’s tooth from his mouth with a pair of pincers, and the King comes back to life, whereupon a man dressed as Little Judy enters to collect the money, while the rest of the cast sing songs and perform a step-dance and a broomstick dance.

In her little history of Idbury, Evelyn Goshawk records several folk rhymes from the village, such as:

Fog on the hill, water to the mill,

Fog in the hollow, fine day to follow.

Another hints at a traditional rivalry between Idbury and Fifield; Idbury, being slightly higher, is often above the fog that shrouds its neighbour:

Fifield steeple wears a cap

Idbury people laugh at that.

She also records the traditional words to the Idbury May Day song, sung by the children as they went from house to house with a veiled May Doll, which they requested small gifts of money to unveil:

Here we come with the Queen of May,

Queen of May, Queen of May,

Here we come with the Queen of May,

All on a bright May Day.

Come please all your money pay,

Money pay, money pay,

Come please all your money pay,

If you see the Queen of May.

Smiling May, come today,

Come today, come today,

Smiling May, come today,

Sing we merrily.

This custom died out before the Second World War, but even in the forties the Idbury and Fifield children went from house to house with boughs of blossom, singing,

The cuckoo is a pretty bird

It singeth as she flies

It bringeth us good tidings

It telleth us know lies

It sucks little birds eggs

To keep its songs all clear

And every time we hear cuckoo

Summer is drawing near.

Besides the folk dances, plays, customs, and rhymes, Idbury had its small stock of local folk tales and legends. Robertson Scott records the most common of these: ‘Several people in Idbury persistently repeat that in old days monks or nuns used to be in the House and the monks used to come by a secret way from Bruern Abbey & that there is treasure buried in the house.’ A grisly version of this legend has robbers seizing a shepherd and his dog and skinning them both alive in this hidden tunnel.

This was not the only secret passage in Idbury – folk tradition also has it that the eighteenth-century highwaymen brothers Tom, Dick, and Harry Dunsden, who came from Fulbrook, had a cottage in Icomb, from which an underground tunnel was supposed to lead to a hideaway in the abandoned quarry in Idbury Copse. This patch of woodland lies at the head of a long rise on the Burford-Stow ridge road; an ideal spot for highwaymen to lurk. Their most daring escapade was to hold up the Oxford-Gloucester coach on this road and make away with £500. Tom and Harry were hung at Over, outside Gloucester, in 1784, for the murder of the tapster, William Harding, who died of his wounds; the landlord of the Capp’s Lodge Inn was saved when a bullet shot by Harry Dunsden was deflected by a purse of coins in his pocket. The oak where their gibbeted bodies were hung as a warning to others still stands, near Capp’s Lodge, their former haunt; it can be seen to the right on the Fulbrook-Shipton road, and still bears the initials TD and HD carved into the trunk. The eldest, Richard, disappeared after a failed robbery at Tangley Hall. Richard thrust his arm through the wide latch hole to unlock the door and while he was fumbling for the key, the servants inside lashed a rope around his arm; he supposedly urged his brothers to cut his arm off with their swords, before they made their get away. Richard was never seen again, and is supposed to have died of his injuries. A skeleton widely assumed to be his was discovered in Idbury Copse, just off the ridge road, by J. W. Robertson Scott, though other accounts claim he was buried by his brothers in a secret grave on Shipton Down. Idbury Copse is supposed to be a haunted place, according to the gypsies, who will never stop near it.

Another local folktale tells of an old man whose wish to be buried in Idbury was thwarted by ice on the road – as the horses pulled the carriage up Idbury Hill from Bould, they slipped and fell, and ever since, it is said, the road has been running with water, crying for that old man.

There may be plenty of water on the roads, but lack of mains water was a source of real worry to Idbury. When Scott arrived the village relied on a 25’ well without a pump; Scott seems to have been responsible for installing a ram, or hydraulic pump, but even that seems to have ensured only an intermittent supply. In the 40s,when Bill Paxford was responsible for managing the pumping station between Idbury and Fifield, I am told that ‘it was just luck whether you got water or you didn’t’.

The rollicking ‘Idbury Water Song’ tells us all about it. This was sung by the local water diviner at a village party at the manor on December 20th, 1923, and pokes gentle fun at their teetotal host.

A million or two years ago, as you’ve read,

When what’s now dry land was the deep ocean bed,

Then places like Fifield and Kingham, and such,

Were covered in water and couldn’t show much.

But Idbury hill stood as dry as a bone,

And that’s why the Romans chose this spot alone

To build them a camp, and they gave it our name,

Thus Idbury rose even higher in fame.

When St. Nicholas sailed in his ship o’er the seas,

He sought for some spot where he might take his ease,

Till one day in the distance our hill he did spy

And he landed at Idbury where it was dry.

In the old manor house, there’s a tunnel, they say.

Down to Bruerne it runs, and the monks went that way;

Yes, they knew what was what is those days long gone by

Thirsty monks wouldn’t stop in a place that went dry.

And even to-day the old place is the same

They promised us water – but no water came,

For unless the rams work, and some days they are shy,

Then Idbury taps will be sure to run dry.

To-night we are dry as we sing, I daresay,

Our host is teetotal although he’s so gay,

But the tank I’ve just heard is full up to the brim,

If there’s nothing for us there is plenty for him.

Unfortunately we do not know the name of the author of this poem; his initials were WSK. In later years, the Strongs at the Merrymouth Inn were the local water diviners.

In the 1920s, Idbury was visited by a number of significant folklorists. The folk song collectors Cecil Sharp, Maud Karpeles, and Margaret Shaw all stayed with the Robertson Scotts at Idbury Manor, as did the great expert on the Japanese folktale, Yanagita Kunio. In more recent years, Katharine M. Briggs, whose books include the definitive four-volume Dictionary of British Folk-Tales and The Folklore of the Cotswolds, lived in nearby Burford; she set her supernatural historical novel Hobberdy Dick, with its abundance of local fairy lore, in the nearby manor of Widford.

© 2008 Idbury. All rights reserved