A Canadian, Frank Prewett was born in 1893 on a farm in Ontario, and brought up as a strict protestant. He attended the University of Toronto, but left before taking his degree to join the war effort. At the same time, he began writing poetry.

A Canadian, Frank Prewett was born in 1893 on a farm in Ontario, and brought up as a strict protestant. He attended the University of Toronto, but left before taking his degree to join the war effort. At the same time, he began writing poetry.

By 1916 Prewett was at the front, serving as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. He was thrown from his horse, seriously injuring his spine, and spent the rest of the year in hospital. Returning to the front as an officer in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, Prewett suffered the horrors of trench warfare under shell fire, which left him with lasting psychological damage. In a letter of 1920 to Lady Ottoline Morrell he writes,

Just a moment ago there was a crash somewhere in the distance and instantaneously I was in a dug-out and the roof had been blown it. It is dreadful how these war experiences cling to one.

Prewett’s most recent editor, Bruce Meyers, describes how in this letter, ‘the handwriting goes wild, the “d”s rise up with three and sometimes four tails shooting into the air like shell-bursts.’

Prewett was invalided out of the army in 1917, and sent to the military recuperation hospital at Lennel House in the Cheviots, where his psychiatrist was the pioneering psychologist and ethnologist, W. H. R. Rivers.

At Lennel, Prewett met the poet Siegfried Sassoon. Sassoon was intrigued by the young Canadian. In Siegried’s Journey, Sassoon writes:

The greatest luck I had was finding among my fellow convalescents one who wrote poetry. His name was Frank Prewett. Everyone called him ‘Toronto’, that being his home town. He was a remarkable character, delightful when in a cheerful frame of mind, though liable to be moody and aloof… His alterations between dark depression and spiritual animation suggested a streak of genius.

Sassoon introduced Prewett into the literary world, writing excitedly about his new protegé to Wilfred Owen at the front and to Lady Ottoline Morrell, the literary hostess whose manor house at Garsington was the place to be seen for up-and-coming artists and writers. Owen responded on October 10th 1918 – less than a month before his death – that he was ‘so interested about Prewett’.

At his best, Prewett’s war poems have something of Owen’s strange intensity, although they are clearly greatly indebted to Sassoon’s sardonic matter-of-factness. One of the most successful is ‘Card Game’:

Hearing the whine and crash

We hastened out

And found a few poor men

Lying about.

I put my hand in the breast

Of the first met.

His heart thumped, stopped, and I drew

My hand out wet.

Another, he seemed a boy,

Rolled in the mud

Screaming, ‘my legs, my legs,’

And he poured out his blood.

We bandaged the rest

And went in,

And started again at our cards

Where we had been.

Ottoline Morrell was also interested, partly entranced by Prewett’s claim to be part-Iroquois, and his propensity for turning up at fancy dress parties in full Red-Indian regalia. Prewett became a regular at the Morrell’s house parties at Garsington – in easy reach of his post-war base as a student at Christ Church, Oxford. She ‘took him up’; Virginia Woolf’s diary, for instance, records an occasion at which Lady Ottoline gatecrashed a party given by H. G. Wells for Charlie Chaplin, with Frank Prewett in tow.

Through Sassoon and Morrell, Prewett met literary lions such as John Masefield, Edmund Blunden, T. E. Lawrence, Katharine Mansfield, W.B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Thomas Hardy spent an entire lunch discussing Prewett’s work with Siegfried Sassoon; he seemed set fair for a glittering career. And what’s more, comfortably ensconced at Garsington, he allowed himself to make amorous advances both to Lady Ottoline and her daughter Julian, as well as to another constant guest, the painter the Hon. Dorothy Brett.

Prewett was drawn by Brett and painted by her fellow-student from the Slade, Dora Carrington. A letter from Carrington to Lytton Strachey records him at Garsington in August 1919, going for a ride with her brother Noel:

We walked over at 9:30 to dear Garsington. As I wanted to see Brett about the furniture. There they were: – all the troupe with their Queen in their midst. Toronto was back again, looking strangely lovely on a great sienna horse, he and Noel went off riding together before lunch.

This happy dream was all brought to an end later that year, when the Canadian Army ordered him home for repatriation. Although Sassoon and Lady Ottoline visited him in Toronto, he felt exiled from literary life; it was at this time that he first took refuge in the bottle, to keep the terrors of shell-shock at bay. In 1921 he returned to England, and published his first book, Poems, hand-set and printed by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press. It was very well received – Virginia Woolf wrote to Lytton Strachey to tell him, ‘The Times Literary Supplement, by the way, says that Prewett is a poet; perhaps a great one.’

Prewett graduated from Christ Church and was set up by Sassoon in a doomed attempt as a farmer at Tubney Farm. It was at this time that he became friends with Robert Graves – then involved in an equally doomed attempt to make a living as a village shopkeeper in nearby Boar’s Hill. In 1924, Prewett published a second volume, A Rural Scene, which disappointed Graves, and these were to be the last poems published in his lifetime.

When the farm failed, Prewett was taken in by Lady Ottoline, and placed in charge of milk collection and cheesemaking on the Garsington Estate. The writers and artists of this period, as shown in Virginia Nicholson’s wonderful book Among the Bohemians, felt that the wealthy should regard it as a privilege to support them; to sponge off wealthy patrons was normal, and any number of ‘loans’ were negotiated with no intention of ever being paid back. Robert Graves cheerfully admits in Goodbye to All That to having overcharged the richer customers of his Boar’s Hill shop, finding the fraud ‘as easy as shelling peas’. Perhaps influenced by his friendship with Graves at this time, Prewett took a similar attitude to Philip Morrell, literally creaming off the profits from the dairy for himself. He even wrote a postcard to Siegfried Sassoon boasting that ‘I have swindled Philip beyond the dreams of avarice.’ The straightlaced Sassoon forwarded the card to the Morrells, and Prewett’s world came crashing down on him. He was summarily ejected from Garsington, never to return. At the same time his first marriage to Madeline Klincard, which had produced a daughter, Jane, also failed.

When the farm failed, Prewett was taken in by Lady Ottoline, and placed in charge of milk collection and cheesemaking on the Garsington Estate. The writers and artists of this period, as shown in Virginia Nicholson’s wonderful book Among the Bohemians, felt that the wealthy should regard it as a privilege to support them; to sponge off wealthy patrons was normal, and any number of ‘loans’ were negotiated with no intention of ever being paid back. Robert Graves cheerfully admits in Goodbye to All That to having overcharged the richer customers of his Boar’s Hill shop, finding the fraud ‘as easy as shelling peas’. Perhaps influenced by his friendship with Graves at this time, Prewett took a similar attitude to Philip Morrell, literally creaming off the profits from the dairy for himself. He even wrote a postcard to Siegfried Sassoon boasting that ‘I have swindled Philip beyond the dreams of avarice.’ The straightlaced Sassoon forwarded the card to the Morrells, and Prewett’s world came crashing down on him. He was summarily ejected from Garsington, never to return. At the same time his first marriage to Madeline Klincard, which had produced a daughter, Jane, also failed.

Prewett was at rock bottom, as far from the literary shooting star of just a few years previously as could be. He was completely dropped by the snobbish crowd that had taken him up so eagerly. Only those who had settled abroad, like Robert Graves and Dorothy Brett, did not withdraw their friendship. Although he did publish a socialist novel, The Chazzey Tragedy, in 1933, and continued writing unpublished poetry, Frank Prewett was now a forgotten man.

Prewett was at rock bottom, as far from the literary shooting star of just a few years previously as could be. He was completely dropped by the snobbish crowd that had taken him up so eagerly. Only those who had settled abroad, like Robert Graves and Dorothy Brett, did not withdraw their friendship. Although he did publish a socialist novel, The Chazzey Tragedy, in 1933, and continued writing unpublished poetry, Frank Prewett was now a forgotten man.

He taught at the Agricultural Economics Research Institute at Oxford, and wrote several books on agriculture, and gave a series of talks on BBC radio on country life, before becoming a journalist. In 1934 he was appointed as the first editor of The Farmer’s Weekly, launched jointly by Lords Beaverbrook and Rothermere. He soon fell out with his employers and walked out of his job, to be tracked down in a pub in Henley by Robertson Scott, who lured him to Idbury as assistant editor of The Countryman.

The combination of teetotal Scott and hard-drinking, snuff-taking Prewett was never a marriage made in heaven, and when Prewett – whose mysterious attractiveness to women had been remarked on by the artist Mark Gertler – moved in with Dorothy Pollard from the circulation department in her cottage in Fifield, he was sacked.

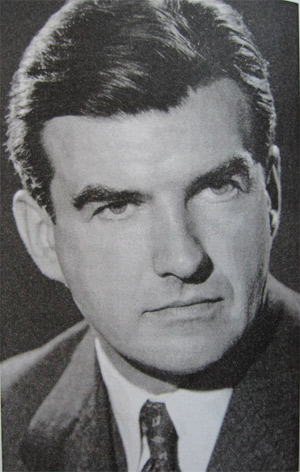

Victor Bonham Carter

Prewett and another disaffected ex-employee of The Countryman, Victor Bonham-Carter (pictured) set up a rival magazine, Country Scene and Topic, but it was a short-lived venture, to Robertson Scott’s undisguised pleasure.

Prewett and another disaffected ex-employee of The Countryman, Victor Bonham-Carter (pictured) set up a rival magazine, Country Scene and Topic, but it was a short-lived venture, to Robertson Scott’s undisguised pleasure.

In the Second World War Prewett went back into uniform, ending the war in Ceylon as Advisor to the Allied High Command in South-East Asia. It was there that he wrote his poem ‘Cold Loving’, subtitled ‘Cotswold from Ceylon’:

Ash and elder, maple and thorn

To grey longwinter wold belong:

Ash last-leafen, first leaf-fallen

Most shows delicate in wold summer-sullen.

No yielding lover you, slowly lovely seen:

Your love is ask of frost, of northing keen,

Long-tarried spring, defeated flowers:

Brazen the loving once was ours.

I in this tropic richness where abound

Sweet waters and the palm, more fond

Would wold-faithful afar choose be there

And ash and elder and the thorn be bare.

After retiring from the Air Force for health reasons in 1954, Prewett live a quiet life in Fifield with his second wife Dorothy – always known as Polly – by whom he had a son, William. That year he wrote to Dorothy Brett:

I live in a cottage in this remote Cotswold hamlet, and desire to be nowhere else, except to travel a month or two in the Far East or America, and sink again into the Cotswold quiet.

I see no one of those we used to know. I have been a good deal abroad, but my isolation even so is largely of my own choosing. I am sufficient in digging, reading, and writing.

According to Bruce Meyer, ‘Prewett spent his last years growing vegetables and cacti, raising tortoises and living in an unheated garden shed attached to his house in Fifield.’ The house was next to the church, and is now, much-altered, known as Old Housing.

Prewett died in 1962; almost the last thing he understood before he finally lost consciousness was that Robert Graves had undertaken to see his unpublished poems into print, which he did in 1964, in a volume rather misleadingly called The Collected Poems of Frank Prewett. This contained only 6 poems from the two books Prewett published in his lifetime, Poems and A Rural Scene. Both of these volumes are scarce and sought-after now.

The diagnosis of those sent to be treated by W. H. R. Rivers was not shell-shock or post-traumatic stress, but neurasthenia – literally, weakness of the nerves. This is not a term in current psychiatric use, but it is a useful onefor someone of Frank Prewett’s highly-strung temperament. From the evidence of his poems he seems to have been a man who could be assailed at any moment by a kind of universal dread – a daylight version of night terrors.

The following poem, about crossing the ridge road between the valleys of the Windrush and the Evenlode shows this aspect of Prewett’s mind well. Its title is ‘The Cloud Snake’:

As I came at dusk to the hump of the wold

I must cross in the sun’s afterglow,

A black snake of cloud stretched itself on the ridge

And I was afraid to brave it for the valley below.

Beyond lay the lighted lowland where I would be,

And lighted behind me was the sister vale:

Dark only the ridge under the snake of cloud

And cold the subtle east wind at its tail.

My shelter lies in the moonlight beyond,

I am not daunted by a snake of black.

So I run onward, so runs the cloud before,

Trailing the frosted east wind in her track.

The blue stars dance before me and behind,

Beneath them I know the east wind is not cold.

Do not freeze and fear me on this height,

I only seek to pass from vale to vale of the wold.

Prewett said of his own poems that they have ‘a hard but true music, and do not belong to the cant of the age’. Another way of putting this is that he was a poet out of step with his times, who continued crafting well-wrought Georgian lyrics long after the poets of the thirties had made such writing irrelevant.

Despite Graves’s contention that he was ‘among the few true poets’, Frank Prewett will only be remembered as a footnote in Canadian and Cotswold literary history. But he deserves at the least everything he asks for in his poem ‘Plea for Peace’:

A steep valley overhung by trees

And a ditch ripple, noiseless, nosing its way

Where dwell all seasons quiet and at ease,

Nor bird nor shine but comforting peace all day.

Let the plain be bare, wide and lone

That hides the valley, the noiseless rill:

Brack be the water, slippery the stone

So there be peace, peace and quiet still.

© 2008 Idbury. All rights reserved