In J. W. Robertson Scott’s visitor’s book-cum-commonplace book from the 1920s, called The Idbury Book, is a line of music with the signature of the writer Sylvia Townsend Warner, dated 29 August – 28 September 1924. Townsend Warner was 31, but her literary fame was still to come. She was staying in Idbury, in fact, to complete her first novel, still her best-known work, Lolly Willowes (1926). She had rented a cottage from the Robertson Scotts. In her essay ‘The Way I Have Come’, first printed in The Countryman in July 1937, and reprinted in the Journal of the Sylvia Townsend Warner Society in 2007, she describes how ‘in The Nation, I read an advertisement of a cottage to let, with “privacy and electricity”. I liked the idea of such a conjunction. What I found when I arrived to take possession was even better. For the cottage was at Idbury and its lessors were John and Elspet Robertson Scott.’

In J. W. Robertson Scott’s visitor’s book-cum-commonplace book from the 1920s, called The Idbury Book, is a line of music with the signature of the writer Sylvia Townsend Warner, dated 29 August – 28 September 1924. Townsend Warner was 31, but her literary fame was still to come. She was staying in Idbury, in fact, to complete her first novel, still her best-known work, Lolly Willowes (1926). She had rented a cottage from the Robertson Scotts. In her essay ‘The Way I Have Come’, first printed in The Countryman in July 1937, and reprinted in the Journal of the Sylvia Townsend Warner Society in 2007, she describes how ‘in The Nation, I read an advertisement of a cottage to let, with “privacy and electricity”. I liked the idea of such a conjunction. What I found when I arrived to take possession was even better. For the cottage was at Idbury and its lessors were John and Elspet Robertson Scott.’

This cottage was almost certainly the one now known as the Thatched Cottage, which the Scotts acquired with Idbury Manor. Certainly it could be Lolly’s cottage in the book:

Tea being done with, Laura took stock of her new domain. The parlour was furnished with a large mahogany table, four horsehair chairs and a horsehair sofa, an armchair, and a sideboard, rather gimcrack compared to the rest of the furniture. . . On either side of the hearth were cupboards, and the fireplace was of a cottage pattern with hobs, and a small oven on one side.

Lolly Willowes is the story of a spinster who finds her vocation as a witch. As she tells the Devil

It’s like this. When I think of witches. I seem to see all over England, all over Europe, women living and growing old, as common as blackberries, and as unregarded. I see them, wives and sisters of respectable men, chapel members, and blacksmiths, and small farmers, and Puritans. In places like Bedfordshire, the sort of country one sees from the train. You know. Well, there they are, child-rearing, house-keeping, hanging washed dishcloths on currant bushes; and for diversion each other’s silly conversation, and listening to men talking together in the way that men talk and women listen. Quite different to the way women talk, and men listen, if they listen at all. And all the time being thrust down into dullness when the one thing all women hate is to be thought dull.

At the time, Sylvia Townsend Warner was known as one of the editors of the 10-volume Tudor Church Music, and as an up-and-coming poet. She wrote a number of poems both in and about Idbury, including ‘Country Thought’, which appeared in Time Importuned (1928):

Idbury bells are ringing,

And Westcote has just begun,

And down in the valley

Ring the bells of Bledington.

To hear all these church bells

Ring-ringing together –

Chiming so pleasantly,

As if nothing were the matter –

The notion might come

To some religious thinker

That the Lord God Almighty

Is a travelling tinker,

Who sits retired

In some grassy shade,

With a pipe – a clay one –

And plies his trade,

A-tinkling and a-tinkering

To mend up the souls

That weekday wickedness

Has worn into holes:

And yet there is not

One Tinker, but Three –

One at Westcote, one at Bledington,

And one at Idbury.

Other poems written in Idbury include ‘The Virgin and the Scales’, ‘Upon a Gentleman Falling Seriously in Love’, ‘A Song about a Lamb’, all published in her first collection, The Espalier (1925).

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s stay in Idbury was brief but important, both because it was a pivotal time in her development as a writer and because of the influence that her landlord J. W. Robertson Scott had on her politics. She had already read Scott’s trenchant articles on rural affairs published in The Nation under the ironic title, ‘England’s Green and Pleasant Land’. She may also have been previously acquainted with Scott through some mutual friend such as Gustav Holst. But whether they already knew each other or met accidentally as tenant and landlord, Robertson Scott’s powerful personality helped shape Townsend Warner’s frankly Marxist political views on the rural economy of Engalnd. In his book about Tyneham in Dorset, The Village That Died for England, Patrick Wright writes about the village of East Chaldon, home to the writer T. F. Powys, and from 1930-37 to Sylvia Townsend Warner and her partner, Valentine Ackland. It was from Robertson Scott, he writes, ‘that Townsend Warner had first grasped how much a programme of educational and cultural activities could do to enliven a demoralised village. Idbury had been “a melancholy little hamlet, full of picturesque cottages that had gone bad”. But Robertson Scott, who was well aware of the need to cut through the “prettyish seeming” of country life as perceived by “the week-ending classes” and to address the “haggard reality” underneath, was taking steps to revitalise the place.’

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s published diaries contain only two references to Robertson Scott, but they show that she remained on visiting terms with him in 1950. Her published letters contain just one from ‘The Manor House, Idbury’, on the 10th of November 1924, to the writer David Garnett, who had just made his name with the magical novella Lady Into Fox, set just round the corner in Tangley Hall.

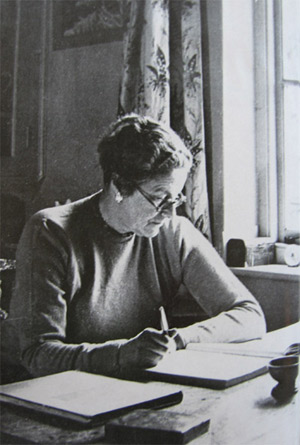

She remains a greatly underrated writer, whose quiet wit infuses both her prose and poetry. 2008 saw a visit to Idbury from the Sylvia Townsend Warner Society, and the publication of her New Collected Poems, edited by her biographer Claire Harman, in which all of her poems written in and about Idbury may be found.

2008 Idbury. All rights reserved